Being able to read music is an extremely powerful skill.

For myself, growing up, I played piano and ukulele. I relied very heavily on my ear to learn how to play songs. I’m very thankful for my ear, but this really limited me in the types of songs I could play.

So, for example, whenever I would visit my grandparents, it wasn’t uncommon they would want me to play a hymn on piano for them, or if it was around Christmas, a carol. They would put the songbook in front of me, and unless I knew the hymn or carol from memory, I would freeze or have to fumble my way through it.

Whenever I looked at a piece of music, I was completely intimidated by it.

How to Read Music

Looking at the sheet music of a song you’ve never played or heard before can be a little overwhelming, but it shouldn’t deter you from learning the song.

After this post, you’ll be reading music like a champ.

The Musical Staff & Notes

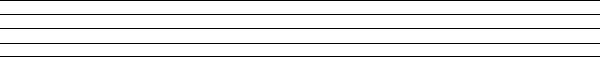

A piece of written music is built on the staff. The staff is a set of five horizontal lines that run across the page of a sheet of music.

Musical notes are placed are either right on the lines or in between the lines.

Notes that fall below or above the staff are placed on ledger lines.

Treble Clef & Bass Clef

Notes placed higher on the staff are higher in pitch, while notes placed lower on the staff are lower in pitch. Makes sense.

Note values are represented by the first seven letters of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, G.

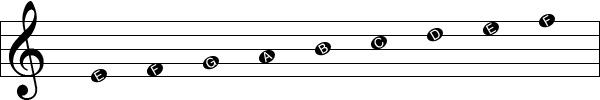

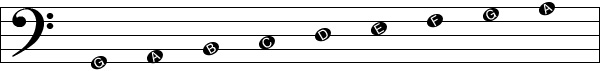

Where these note values are placed on the musical staff depends on the clef. There are two types of clefs: treble and bass.

The treble clef is represented by a big “G” shaped letter at the beginning of the staff. As ukulele players, we will be frequently using the treble clef to read music.

The bass clef is represented by a curve with two dots to the right.

If you’ve ever seen a piece of piano music, the bass clef is written below the treble clef. Instruments that play in a lower range like a bass guitar, trombone, or tuba will use the bass clef as well.

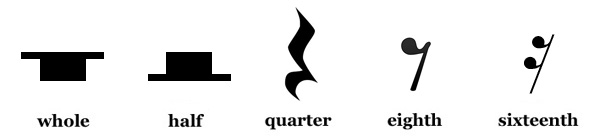

Note Lengths

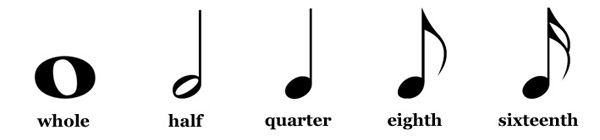

As seen above, the position of a note on the musical staff determines its pitch. There are different types of notes to determine the duration or how long a note is played.

A whole note is the longest note sounding out the entire duration of one measure.

A half note is half the duration of a whole note. This means two half notes = one whole note.

A quarter note is half the duration of a half note. This means two quarter notes = one half note; or four quarter notes = one whole note.

An eighth note is half the duration of a quarter note. This means two eighth notes = one quarter note.

A sixteenth note is half the duration of an eighth note. This means two sixteenth notes = one eighth note; and again, to take it even further, four sixteenth notes = one quarter note.

These are the most common note lengths.

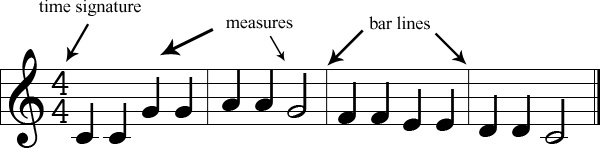

Time Signatures & Bar Lines

As you can see, there is some math behind playing music. Whenever you play a song, the song is based around a consistent timing structure.

This count is dictated by a time signature.

A time signature is a pair of numbers at the beginning of a song that lets you know how a song is counted.

Here are some common time signatures:

The number on the top tells you how many beats there are per measure. The musical staff is separated into measures with vertical bar lines.

Take a look at this example. This is the first four measures of “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.”

The number on the bottom tells you what kind of note length each beat gets.

For example, in a 4/4 time signature, the most common time signature, there are four beats per measure and each beat gets a quarter note in length.

In a 6/8 time signature, there are six beats per measure and each beat gets an eighth note in length.

The most important number is the top number because that tells you how you count the song.

Rests

Some of the most effective parts of a piece of music can be when the music stops and nothing is played at all.

When you look at a piece of music, you might see some rests. When you see a rest, that means don’t play!

Rests have equivalent durations to other regular notes.

That means when you see a whole rest, you rest for a measure.

When you see a half rest, you rest for half a measure.

When you see a quarter rest, you rest for one beat.

When you see an eighth rest, you rest for half a beat.

And when you see a sixteenth rest, you rest for a quarter of a beat.

How to Put All This Into Practice

By now, you’re pretty well equipped to look at a piece of music and have a sense for what’s going on. You might print off this page so you can refer to it later.

There are still some things we haven’t discussed like key signatures, dots and ties, and accidentals (sharps and flats). I want to save some of these things for future posts where there will be more application of all this theory.

Right now, this is just head knowledge, but I really wanted to do this post because I’ve been getting a lot of requests for more fingerpicking lessons and songs, and in order for me to teach those, we need to make sure we know how to read music.

While I’ve done lessons on fingerpicking Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” and fingerpicking the 12-bar blues, what I get asked most about is solo fingerpicking songs–songs where you can fingerpick the melody of the song without singing.

To teach and demonstrate these songs, we need to make sure we have an understanding of some of the basics of reading music.

Next week, I want to look at a really simple song we can fingerpick on the ukulele and exercise our newly acquired music reading skills.

I can’t wait to get more into this stuff with you all. It’s going to be fun!

Your Questions and Comments

Whenever we’re looking at music theory, I know there is bound to be questions and input. Don’t be shy. Post your comments below!