photo by alonis

What are scales? How does a scale work? Why are they important to know?

We’re going to tackle these questions. In this lesson, I want to take an introductory look to scales, specific to the ukulele. This little bit of theory is very helpful to know, and it’s pretty easy to understand.

What is a Scale?

In the simplest way, a scale is a collection of pitches, represented by the letters A through G of the alphabet, arranged in an ascending or descending order.

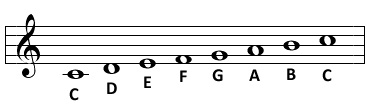

C major scale

There are many different types of scales (e.g. major, minor, pentatonic, etc.). The type of scale will depend on how the intervals are arranged between each note of the scale. An interval refers to how far one pitch is separated from another pitch.

The intervals we want to concern ourselves with are half step and whole step intervals.

On the ukulele, if you play the note on the 2nd fret of the top string and you move up to the 3rd fret, you’ve went up in pitch by a half step. Every time you move up or down a fret you’re moving a half step.

If you play the note on the 2nd fret of the top string and you move up to the 4th fret, you’ve went up in pitch by a whole step, which is equal to two half steps. If you went from the 4th fret to the 2nd fret, you’ve went down in pitch by a whole step.

So How Does a Scale Work?

The arrangement of these half steps and whole steps in the scale gives it a particular quality (e.g. major, minor). Some scales possess larger intervals within them, but the most common type of scale in popular music is the major scale, which can be understood in a whole step and half step pattern.

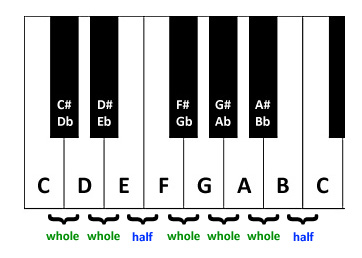

The notes in a major scale are all separated by whole steps, except there are half steps between the 3rd and 4th scale degree, and the 7th and 8th scale degree (the 8th scale degree is the octave note of the first or root note of a scale). See how a C major scale is represented on the piano.

If we know where the half steps and whole steps are on a scale, we can construct any type of scale starting on any note.

For example, say we wanted to construct a G major scale. We can apply the half step, whole step pattern of a major scale starting on a G note.

If we go up a whole step from G, we land on A. If we go up another whole step from A, we land on a B note. Now, we need to go up a half step from B, which will put us on a C note. From the C, we’ll go up a whole step to the D. If we go up another whole step, we land on an E. And another whole step, we end up on an F#, and from F# we go up a half step to get back to G.

So in a G major scale, we have the following notes:

G, A, B, C, D, E, F#, G

When seeing and understanding the construction of a scale, it can sometimes be helpful to look at piano keys to see more clearly the half steps and whole steps between notes. One really great exercise is to construct major scales for all twelve keys.

Why are Scales Important to Know?

Having an understanding of scales allows us to have a framework for which to understand the chords or songs we are playing. Surely, you can play a song from a chord chart without having any understanding of the theory behind it, but if you’re writing your own music, or improvising over a piece of music, this knowledge can be really beneficial.

In addition, understanding scales can be really helpful when you consider adding different quality to your chords such as add9, maj7, diminished, min7, or sus4.

Final Thoughts

We’re only skimming the surface when it comes to scales, but before diving any deeper, it’s helpful to have a basic understanding. Ideally, you want to get to a point where you know in theory all twelve major keys and what notes are in each of these keys. You can start applying this half step, whole step pattern construction to any note to create a major scale. Give it a try and let me know how it goes for you.

We’ll be sure to look at this more in the future.

Are you lost or confused? What are your tips for understanding scales? Post your questions and comments below. Let’s hear it!